NAIZA KHAN trained at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford University. International shows include her first solo museum exhibition, Karachi Elegies at the Broad Museum, Michigan, 2013 and the 9th Shanghai Biennale, 2012. Khan curated The Rising Tide: New Directions in Art from Pakistan 1990 – 2010 at the Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi, 2010. She is a recipient of the Prince Claus Award, 2013, and is currently Professional Advisor at the Visual Studies Department, Karachi University.

The tools in my art practice are intrinsically linked to the direction my work is taking and the questions I am trying to raise. I often work with multiple media simultaneously. This process of investigation leads me to rediscover familiar tools and sometimes demands modes of working with new tools.

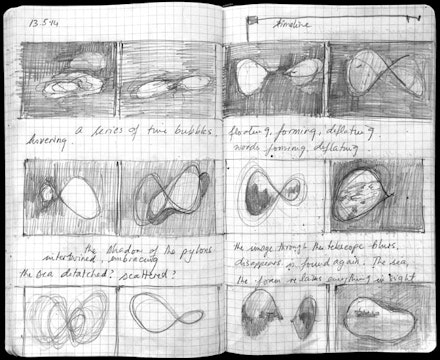

The one tool in my visual research that has remained constant is drawing. This is not only because drawing gives me an instant access to the image in my mind; I feel my ideas become tangible when they are in front of me, not in my head. But more so, drawing has given room for my imagination to flourish, to reinvent and take back an object or emotion and transform it. The emotive and intuitive quality of an idea is the most precious component of my work. But it is difficult to hold onto and easily dispersed.

For over two decades I worked directly with the body, but in recent years my work has grown in directions that I had not imagined. With the changes that occurred, drawing and the fluidity of its language has remained an essential tool in holding together and navigating the paths I have undertaken. These seemingly disparate paths of research were a way of mapping the terrain, a way to reclaim a space—in the case of Manora Island.

My interest in urban space began with the not-so-urban locale of Manora Island, off the coast of Karachi. My seven-year research of this island, its geography, social relations, and built structures, has given me a unique visual and contextual microcosm of the state of flux and transformation that the coastal city of Karachi and this region are undergoing. The port city of Karachi has a strong connection through maritime trade to other mercantile cites in the Arabian and Indian peninsula and beyond. As a mercantile city, it is hybrid, dynamic, multicultural, and impure.

The small island has a long history of inhabitation and possesses various historical and religious sites: the Shri Varun Dev Mandir, the shrine of Yousuf Shah Ghazi, the Talpur Fort, St. Paul’s Church, a Sikh gurudwara, the Manora Lighthouse, as well as colonial-era buildings and modern structures. They point to a multi-religious social fabric that once existed, a site for both Hindu and Muslim pilgrimage, and non-elite leisure.

Its everydayness has a different texture from the frenetic urban metropolis of Karachi. Yet on a quieter scale, it evokes the same play of history, urban decay, and transformation that many cities in South Asia are undergoing.

The process of mapping the island evolved in an intuitive manner. Over random conversations and ramblings through the island, I accumulated a vast archive of images relating to Manora’s heritage sites as well as documentation of the transforming social space. Stepping back from this body of visual material, some found and some produced in my studio, I began to assemble and survey the objects, drawings, photographs, historical text, and video works as an archive of sorts.

I was not sure how to process the imagery as the material I excavated was varied in its form and source and did not fit together. There were narratives of different scale.

I thought about how a drawing can create points across a surface and stretch the space and its meaning. Similarly, I was thinking of myself, drawing and plotting lines across the physical terrain of the island, with my body traversing from one point to another, each time creating a memory, another dialogue with a built structure or a situation. There were linkages that were unscripted and unresolved between all these points.

So it was through drawing that I could connect the many clusters of ideas that overlapped as well as the material generated through the experience of this site. Drawing allowed me to read through the image into something that the image carried, which had multiple relations.

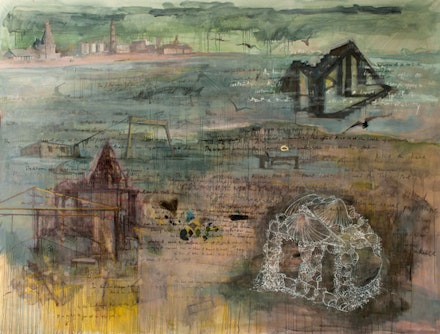

Installing the Manora Archive for the first time at the Shanghai Biennale (2012) offered a way to realign the boundaries so that the narrative could be recounted/reconstructed/remembered. I wanted to take a discursive approach to enable the viewer to create a site map of forgotten histories.

During these last few years, I began to work with film and video, a new tool, which had been rather intimidating to me previously. On my visits to Manora Island, I found it was a way to record the relationship of historical sites to their present decay and conversations with the residents, which I feel are valuable testimonies of the changing social fabric of this region. I am becoming more intimate with the medium and find it occupies a special place in my toolkit.

Working on the editing process, I feel for the intricacy of this medium and how a moving image can be constructed. I am fascinated with the possibilities it gives my work: to stretch time across different planes, moments, and histories. It has opened up the way I think about narrative within my oil paintings and how it can be manipulated within a moving image. It is spatial and temporal and emotive.

I have not rejected any tools, but I did leave oil painting for almost 15 years, only to return to it in 2011. I felt I was coming back to an old love, rediscovering it anew. The desire to paint was strong, it is a slow technology and this was attractive to me. I wanted to narrow down my tools and focus on my work through one medium alone rather than working in multiple processes. A number of large-format oil paintings including “Between the Temple and the Playground”and “The Streets are Rising,” developed between 2011 and 2013. Working with oils again has deepened my engagement with the process of image- making. It has given me the possibility to paint and re-draw the surface and stretch the space beyond what was real. I feel I can pull together ideas that are generated through other sources of research and modes of working. The process has allowed me to think about terrain and landscape as simultaneously a mythic and real experience, in which many sites can overlap.