GUY GOLDSTEIN was born in 1974 in Haifa, Israel and currently lives and works in Tel Aviv. Goldstein’s work has been exhibited at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Hertzliya Museum, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Petach Tikva Museum, KW Berlin, Venice Biennale 2013, AU Museum in Katzen, Art Center in Washington D.C., and Omi Sculpture Park in New York as well as in many international galleries, museums, and art fairs. He won the prestigious Minister of Israeli Culture Award in 2012. Goldstein currently serves as the director of The Visual Communication Department at Musrara, School of Photography and New Media, Jerusalem.

What new or old tools are you

attached to in your art practice?

In recent years, my works are created by transitions between media, attempts to convert and translate actions through one medium to another.

These transitions are sweeping distortions, collecting residues and traces from their own past lives.

While doing these conversion actions, I find myself going through processes of losing and regaining control by empowering the potential of random accidents to occur.

The result, at the end, is like a compression of the process which can indicate the distorted history and narrative that the work has gone through.

Alongside being a visual artist, I am also a musician; I play the bass.

In my works I use sonic elements and sounds, accompanied by drawings and notations. While converting between drawing to sound and vice versa, I use software that are based on an old, cumbersome Russian machine from the 1940s, which made it possible to obtain a visible image of a sound wave, as well as to realize the opposite goal synthesizing a sound from an artificially drawn sound spectrogram.

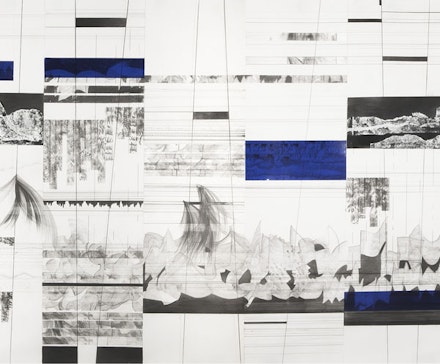

I draw “sonic codes,” sometimes long “timelines” which seem like scores or even like panoramic or aerial land maps, or in a different series, large-scale drawings that seem like spectral waterfalls. I then convert them to sound, using these software, creating animation films with the images from the drawings and its own sound. These actions refer to and remind us of old-school sound artists and sound animators from the 1930s, like Arseny Avraamov (Russia) and Oskar Fischinger (Germany), or even later from the 1950s like Norman McLaren (Canada) who tried to draw sound, animating graphic shapes into sound and creating animation films, combining the animated sound signs on the sound slots of the film.

Once I have the sound of the drawings, I perform with it, playing the bass. Sometimes I invite other musicians to perform and play live with the drawing’s sound on the background. I did it with a theremin player, drummer, and cellist. Thus, a dialogue of harmony, melody, rhythm, and sound is being created out of acoustic, digital, and analog instruments and tools.

To create the drawings I use various drills, equipped with graphite and pencils instead of its bit.

The sound and vibrations of the drill transfer onto the paper as rich patterns and textures. Then, using a tape, I transfer these textures to a different part of the drawing or to other drawings on a separate sheet as an act of recording. The graphite sticks to the tape and with it I can compose. I accumulate layers and edit these tapes as voiceprints, graphic notation, or spectrographs.

To end this process I convert the sound of the drawings to image again, by using the same software. The final result is a ghost of my images, inverted black and white distorted images of my original drawings. When I look at these images I understand that the main tools I use are all physics and mathematics.

My works do not reveal and expose the tools with which they were created. The viewer can “see” the music, hear a sound, feel the frequency through the drawings, and can recognize a history, a process, and a distorted narrative the work has gone through but cannot name the tools or the technique I used.

What tools have you rejected?

Among the classical and fundamental tools at an artist’s disposal, I am very careful in using colors and figurative images. I need a good reason to use these two visual tools. It is something that I came to understand recently, when I looked at the evolution of my works. In my earlier works there are some series of figurative drawings and objects. It referred to the themes and topics that I was attracted to at the time. Recently, my works are less concerned with a certain theme or subject, they are more about the process, the issue of “time,” stretching and compressing time, the relations between the viewer and the works through “time.” Therefore, my work becomes more abstract, I don’t have motivation to use pictorial images or a rich palette anymore. Using a certain color, I am usually motivated by a conceptual idea, like the “Colors of Noise” theory which I am leaning on recently. My forms and shapes are mostly a result of the accidents that I encourage in a limited, defined range within my process.

What have the tools

done to your art?

I think, as time goes by, my tools are more focused and I approach my art with more simplicity. This allows me to create a language that in time becomes clearer. This process consists of collecting tools, writing language, and then connecting letters to words to sentences. The more I create and “sharpen” my tools, the more I can put together a meaningful combination of visual, conceptual, and emotional experiences.