KEN OKIISHI is an artist who lives in New York.

What new or old tools are you

attached to in your art practice?

In a world where easily circulatable image files of artworks have become interchangeable with, or even more present as the artwork than the physical work itself, there is often a feeling of seeing an artwork in person as a simple identification within a mentally plugged-in database.

In the art-historical realm of “video art” that is the primary genealogy that my own work works out of, this problem leaps in multiple directions at once. Video, as a medium which intrinsically has a technological material but also distributable container through which it is recorded and viewed, is one of the few art mediums that can have its full presence felt in dramatically different locations and viewing conditions at the same time. While it is true that the best projection from original formats at MoMA versus a low-resolution streamed image are visually and aurally different, in a work such as VALIE EXPORT’s Asemie or the Inability of Expressing Oneself Through Facial Expressions (1973), the presence of the artwork rips through all compressions and distributions of the moving image, no matter how low or high the resolution. This cannot be said for Pasolini’s films from the 1970s, for example, which are miraculous in the movie theater and basically unwatchable on the computer screen. While the main formal issue here may be scale—but also how light is produced and recorded through film versus video—the transportability of the “presence” of the artwork is what interests me. Through the “envy” of what is behind the multiplicity of screens that we cuddle with and peer through all day long, the “other” side of the screen—the one we live and work on—has started to feel exceedingly flat and deadened. Our minds feel a rush of pleasure as we see one of our friends doing something “epic” or “cool,” but then the finger slides down the screen and maybe there is the most devastating email—and that devastation also feels evacuated of physicality, even when you start crying. It’s all of these things that happen on one side of the screen that have the potential to jump onto the other: somehow the directness of the video-art medium allows jumps in physicality between both sides of the screen, of the transmission of “feeling,” in a way that film requires the scale of the movie screen, or a painting requires one to be there in person with the singular object, or Instagram produces a “viewing experience” that is simultaneously immediate and unreachable. Photography, as a medium, is the most disordered in our present moment. It probably requires the most work in order to be seen as different “in person” than in its screen image. Medium-specificity in our current media-system throws the analytical mind into feedback loop hell. But it is worth the work, to become alive.

There is an urgency, at the moment, in our ever-tightening range of feelings in visual experiences, that artworks make us aware of the multiplicity of different modes of seeing and feeling, and that those differences are made distinct and distinctly material.

What tools have you rejected?

I reject all “pure” tools, since those fail to bring the viewer to life. (The viewer, for me, is an automaton that can become a “real human.” I like this old-fashioned image of the robot—the automaton—because it is still so easy to project feeling into its eyes. Have you seen these cheap robot dogs they sell at flower stores, that have these very tender eyes? It’s amazing how, no matter how low- or high-tech a robot is, it has to have these basic mechanistic movements on some level, and these tender-looking eyes, or it looks absolutely emotionally impenetrable. The way certain overly-rendered animations have the slickness of the screen they are watched on, as if the skin of everything depicted is impervious to communication—certain machines have that presence in real life. I reject emotionally impenetrable machines as well.)

What have the tools done to your art?

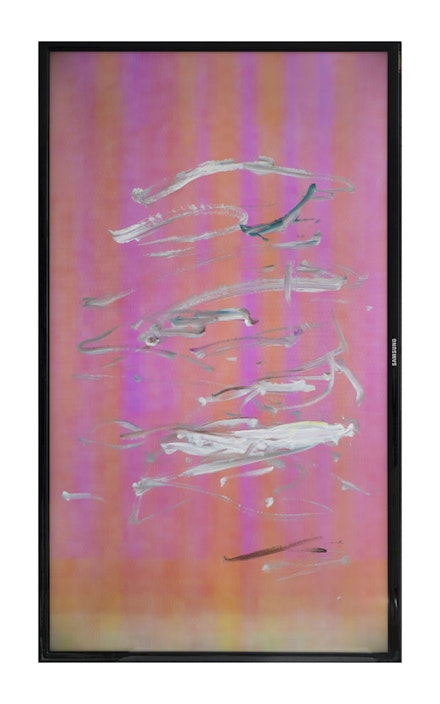

At a certain point video allowed me to re-script my own life, to become something else in relation to the media-systems that organize being. In my recent work, the simultaneous being of unbridgeable media and ways of working has ruptured vision in this particularly satisfying way. I love watching people look at these screen-agglomerations. As the poet Jeff Nagy wrote in a review of one of my recent exhibitions:

A visitor born under the sign of the iPhone’s internal accelerometer might find herself fighting off a manic urge to pull the screens off the wall and shake them until the snippet of a Food Network cooking show or an ad for a decade-old Honda or a few seconds of 60 Minutes automatically rights itself. Despite the paintings’ portrait-oriented similarity to comically outsize smartphones, the archive they screen stays landscape. They refuse to respond in the ways we now expect from our media technologies. […] In their literal détournement of the screens that facilitate our conspicuous consumption of “the present,” Okiishi’s paintings [on flat-screen televisions] create a tension played out in the viewer as the wagged dog of an immediately graspable conceptual gesture—a tension that is genuinely moving and feels perversely like relief.