Johanna Fateman is a writer, musician, and owner of Seagull Salon in New York City.

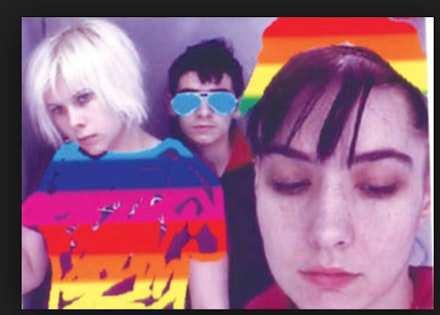

In the early ’90s, I wanted to be a cyborg. So did all my friends, and according to Donna Haraway, we already were. “By the late 20th century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism,” she writes in the book we were obsessed with, her 1991 Simians, Cyborgs and Women. But we were punk girls—riot grrrls—in the Pacific Northwest, and the dominant aesthetic of our small scene was a semi-ironic, scavenged retro-’60s thing: cat eye glasses, thrift store typewriters, fuzzy surf guitar riffs, etc. We didn’t have Hotmail accounts yet, or exactly understand what Haraway meant by “cybernetic,” so her socialist-feminist vision of a post-gender world was distant and abstract.

Then I moved to New York and went to art school. I got into other things: the recent history of appropriationist art, techno parties, home recording. Kathleen Hanna moved here when her band Bikini Kill broke up—we’d lived together in Portland, and played basement shows in a short-lived band called The Troublemakers, named after G.B. Jones’s cult film—and we wanted to make electronic, sample-based music. We started Le Tigre in 1998, I think.

It wasn’t until after our first album, though, that I got my Akai MPC60, the sampling drum machine that changed my life. A substantial piece of equipment, bulky by today’s standards, it felt like a small section of a spaceship console that I’d managed to detach and install in my bedroom. I loved its little buttons and 16 mouse-gray pads. During the day I worked at the alternative art gallery Thread Waxing Space, and when I got home I’d eat candy and stay awake as long as I could, figuring out how to knit beats from tiny pieces. I’d take sounds from 7˝s and CDs, record myself tapping the window or closing a book, then edit and maybe reverse or detune each sample before assigning it to a touch-sensitive pad. The fetishized glitch was peaking as an underground music/art-world phenomenon around then, and I suppose I was somewhat into the ideas associated with that—of incorporating digital artifacts and the traces of software malfunctions into my music. But sometimes the MPC would give me unexpected results, like a stuttering vocal or a crackling sound on the backbeat, that didn’t seem like glitches. They seemed cool and intentional contributions. I’d get a shiver and feel the flowering of new neural pathways when that happened. It felt totally cyborgian.

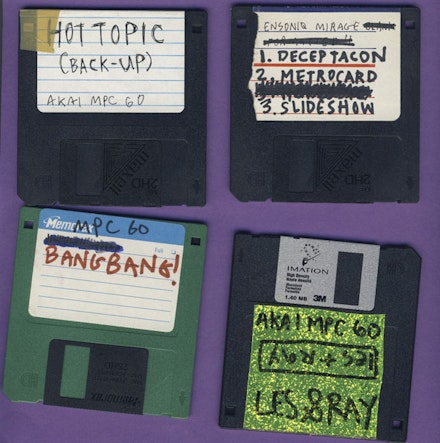

The MPC60 revolutionized the collaborative dynamic of Le Tigre. When Kathleen got one too, we started meeting up at Au Bon Pain on my lunch break to exchange floppy disks. It was a precursor to contemporary remote collaboration. We didn’t have high-speed Internet, cloud storage, Google docs, or Skype, but I could take the disk she gave me out of my purse, load her sounds and patterns, and see her ideas exactly as she’d left them for me.

You could say I’ve rejected the MPC. It’s a totally outdated, unwieldy tool I don’t use anymore. But, I could never get rid of it. I mean that I could never bear to sell it or throw it out, but more profoundly, I mean that it’s part of me. I’ve internalized its structure. Each new drum machine or piece of music software I subsequently learned to use, I translated back into the MPC’s terms. When I want to figure out the BPM of a song, I hit its “tap tempo” button in my mind; when I think of a beat, I picture triggering samples on a grid of gray pads. It also set a standard for me, for what I want from technology in my art practice. I look for things that will facilitate collaboration. Ideally I want things that might feel like collaborators—sort of.