For nearly 40 years, HOMER FLYNN has been involved with the murky aesthetics of San Francisco’s music, performance, and video group, The Residents. As their chief visual designer and co-owner of The Cryptic Corporation, The Residents’s business and public relations interface, Flynn has been involved in nearly all of the group’s improbable projects since the mid-1970s. Currently, he lives in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco with his charming wife, Leigh Barbier.

As the primary designer for The Residents over the past 40-plus years, I have seen my tools evolve in many ways, but the primary change, as for many artists, has been from analog to digital. Regardless, I still think the tools to which I’m most attached, both literally and figuratively, are my hands, and the ways that I use those tools have changed dramatically.

In the ’70s and ’80s, those hands used a darkroom, an obsolete idea discarded over two decades ago, as a primary tool. As my methods evolved, rather than dipping themselves into foul-smelling, toxic chemicals, my hands learned to manipulate a mouse as I shifted my work to Photoshop. After moving away from traditional darkroom and photo techniques in the early ’90s, I found that 20 years of analog experience enabled a nearly effortless transition into the world of digital darkrooms. Dodging and burning were similar processes in both, and an airbrush was still an airbrush; in addition, the new digital tools were not only easier to use, but they added the unforeseen pleasure of “undo.” The workflow was faster, more relaxed and less toxic—what’s wrong with this picture, as they say.

And the answer, quite simply, was the residue. Working in graphic arts means the final result is a printed piece and nothing competes with digital tools as a path to achieving high-quality graphic output, but the analog path inevitably left charming, if imperfect artifacts in the wake of its less efficient process. Needless to say, there’s not much charm in hanging a hard drive or a DVD on your wall, and even though exquisite prints can be made from digital artwork, there’s a coldness about their precision and perfection that can’t compete with an airbrushed photo revealing the process of actual human handiwork. It’s like seeing a perfect reproduction of a van Gogh painting in a high-quality art book compared to standing in front the same painting in a museum and feeling the visceral quality of the artist’s brush strokes. The art book allows dissemination of van Gogh’s work to a wide audience and that’s great, but being in the presence of his painting reveals magic.

My point is not to criticize digital tools, but to indicate differences, at least in terms of how the tools have affected my process, both in the act of creation and in its wake. In many ways I have found digital tools enhancing my methods by making them more fluid. At this point I can’t imagine writing an article like this without a computer and a word processor. Earlier, I mentioned the idea of “undo.” Nothing has made me bolder and more willing to take chances than realizing that I don’t have to live with the results of a mistake or bad decision. Digital photography is another example of the fluid quality gained from the simple fact that a digital photo costs nothing, leaving an artist open to infinite experimentation. Taking a thousand digital photos of dog turds can be the kind of economical exercise potentially leading an artist to a point of critical mass, unveiling the hidden beauty of canine feces in its heretofore unseen volumetric state. As an artistic statement, such photos could be depraved—or art—or both—but the tool definitely opens new doors.

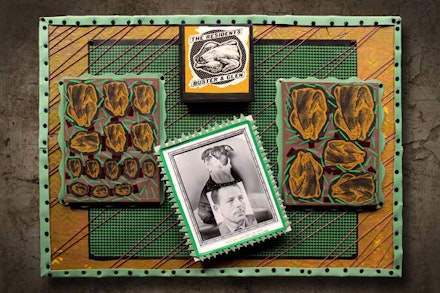

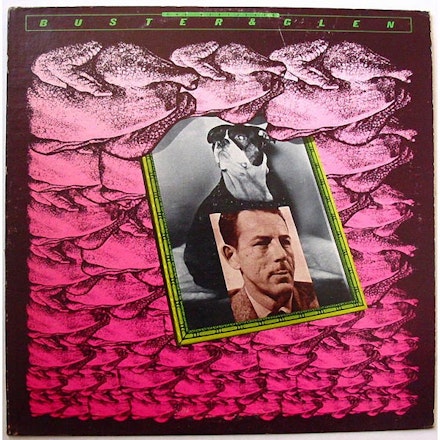

Which brings me back to the tools to which I am most attached—my hands. Back in the days of analog art, my hands were more directly involved in the creative process and in some ways I hunger for that honest “hands on” feeling, and I often look for opportunities to create “real” art. In this context comes another new digitally spawned tool—crowdfunding—an unknown concept just 10 years ago. A major new project involving The Residents has been Theory of Obscurity, a documentary film based on the 40-year history of the group, which was partially financed through the crowdfunding site Indiegogo. The reward offered by the filmmakers for a $10,000 “Executive Producer” contribution was a piece of art created by me. With opportunity knocking, I was only too happy to answer. Dipping into my archive of artifacts, a residue of analog graphics from the 1970s and ’80s, I created a new piece based on Buster & Glen, a fairly obscure EP-length recording done by The Residents in 1978 (“Buster” and “Glen” being a pair of juxtaposed photos existing in the same frame—appropriately, residue of my first marriage). Using a hammer, nails, paint, glue, and a utility knife, I made the attached piece—totally free of digital enhancement.

It made my hands happy.